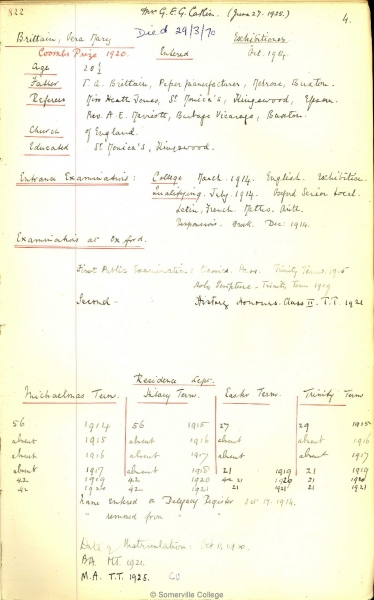

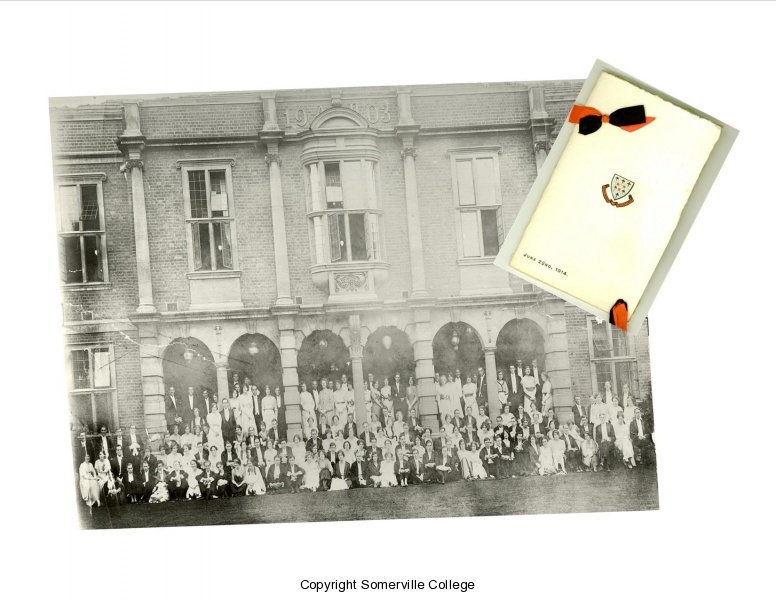

In October 1914, thirty six new students arrived to begin their university careers at Somerville. Amongst these ‘freshers’ were Vera Brittain, the future author and playwright Muriel St Clare Byrne and another English exhibitioner, Una Ellis-Fermor, who would become a distinguished academic. In her diary, Vera Brittain recorded the excitements of student life, her impressions of the University of Oxford as well as Somerville College and detailed the conventions and regulations to which female undergraduates were expected to conform.

“I live in an atmosphere of exhilaration, half delightful, half disturbing, wholly exciting.” Chronicle of Youth, Wednesday 14th October 1914

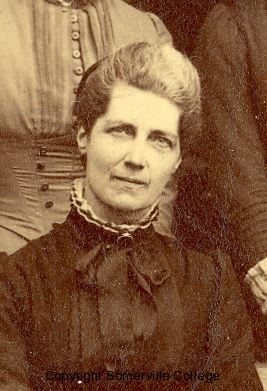

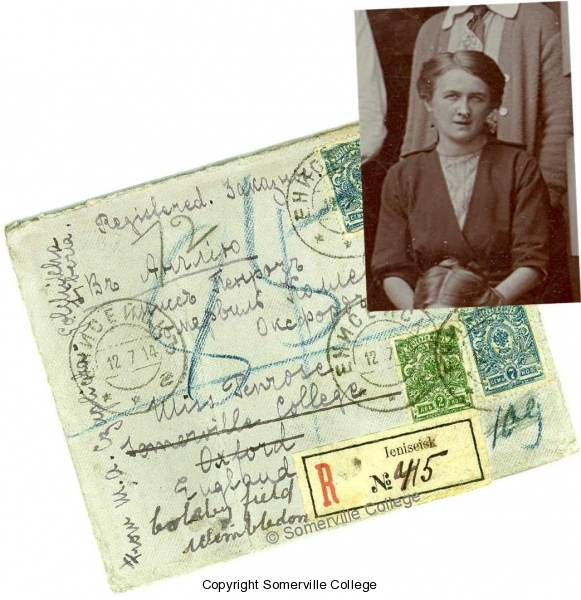

She also recorded her impressions of notable Somerville students such as Dorothy L. Sayers, of the Principal Emily Penrose and of those dons who were to teach her. Members of the SCR in October 1914 included Helen Darbishire, the English fellow and future College Principal, who was to be one of the first women to lecture at Oxford. The Classics fellow, Hilda Lorimer, was of particular interest to Vera; after their first meeting, she recorded a ‘small, wiry, rather astringent person’ who attributed Vera’s lack of Greek to laziness. Miss Lorimer was a leading Homeric scholar, widely travelled in Greece and the Balkans, interested in ‘everything’; Vera described her as “set apart by her own versatility” and soon came to appreciate her kindness and strength of character. Miss Lorimer spent the next four years combining her academic duties with war work, such as translating for the Admiralty, assisting Belgian refugees and, in 1917 and 1918, serving with the Scottish Women’s Hospital Corps in Salonika.

Miss Darbishire is on the left, Miss Lorimer 2nd from right

For Somerville, the new academic year proceeded largely as normal, in great contrast to the men’s colleges, whose numbers were depleted with most of their undergraduates, as well as many fellows and staff, enlisting. Only a few Somerville students did not return in October 1914; one was trapped in Canada as all the steamers were required for transporting troops, another lost her funding which came from Germany and had been seized by the German government when hostilities commenced. Some sought a more active role in the war effort; a second year historian, Grace Procter, deferred her return for a year in order to work for the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Wives Association and Charis Barnett took leave of absence to work as an interpreter for the Women’s Emergency Corps. She did not return to Somerville but went on to become a nurse at a Friends’ Mission in France and worked in the Refugee Maternity Hospital at Châlons-sur-Marne in 1915-1916. She married in 1918 and after the war enjoyed a career in health and welfare, publishing numerous articles and books on birth control and child care.

Charis Barnett was the first Somerville student to abandon her academic life for war work; several others were to follow her lead, most famously Vera Brittain, who was one of the few to return and complete her studies.