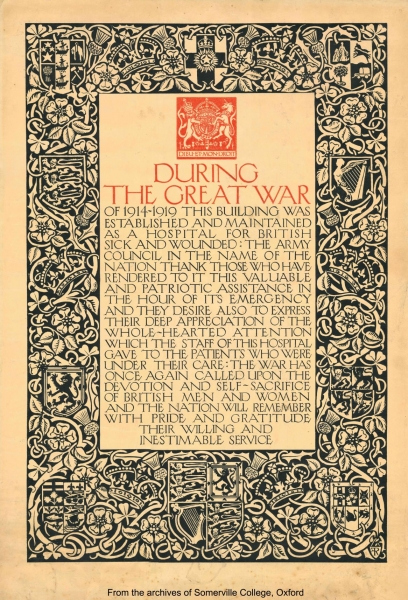

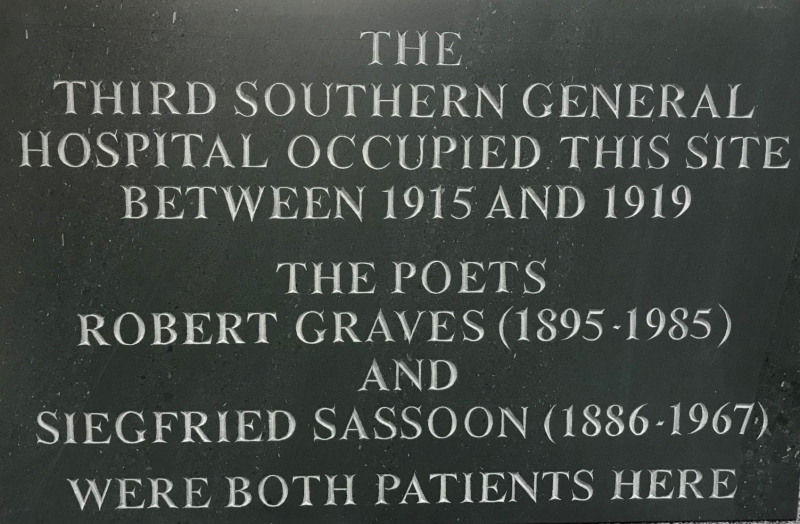

In the months following the Armistice, the military presence in Oxford dwindled and civilian and academic life began to return to normal. Principal Emily Penrose’s immediate concern was the timely return of the Somerville site to the college. Once the 3rd Southern General Hospital had vacated the buildings in the spring of 1919, they had to be repaired and redecorated, the whole process taking twice as long as had been anticipated and allowed for in the lease of 1915. Oriel kindly permitted Somerville to remain in St Mary Hall until the end of the summer term, but returning ex-servicemen were not always pleased to find their rooms occupied, and furniture utilised, by female interlopers. On 19th June 1919, a crowd of revellers ‘celebrating a triumph on the river’, attempted to breach the brick wall built in 1915 to divide St Mary Hall Quad from the rest of Oriel. The pickaxe-wielding invaders were repelled, the hole guarded throughout the night by members of the SCR and the episode passed into college legend as ‘The Pickaxe Incident’.

Of the Somervillians who had interrupted their studies for national service, only two, Vera Brittain and Winifred Holtby, came back after the war had ended. Winifred Holtby [see July 1918 blog], away for just one year and closer in age to the rest of the JCR, resumed her student life with relative ease. For Vera Brittain, it was to prove much more difficult; age and tragic experience created an almost unbridgeable gap between her and her fellow students, most of whom had spent the previous four years at school.

Nationally, the war accelerated social and political change for women, with the extension of the franchise in 1918 and access to the professions via the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act of 1919. Similarly, in Oxford, the conflict had altered the position of, and attitudes to, academic women. Out of necessity, women had been asked to give lectures, admitted to read medicine, relied upon to support the functions of the University academically and financially in the absence of hundreds of male undergraduates and fellows. In Hilary Term 1920, Convocation voted to admit women to membership of the University. To many, this was the crowning achievement of Emily Penrose’s academic career. She had led the campaign for degrees using strategy and personal example. Thanks to her insistence that students should take degree courses and meet the residence and qualification requirements, over 300 Somervillians were eligible to graduate. Among the first to receive their degrees, in Michaelmas Term 1920, were Dorothy L. Sayers, Cicely Williams, Enid Starkie and Margaret Kennedy, as well as the five heads of the women’s houses (although, not fulfilling all the requirements themselves, they received their MAs by decree).

A century later, the impact of the Great War remains a subject of study and debate among historians. Somerville’s first college history, published in 1922, concluded:

“The ability shown by women in their response to war emergencies has prompted recognition from many unforeseen quarters….. [Somerville’s] record was one of efficient service which contributed, no doubt, in its infinitesimal way to victory. But war psychology is such that victory itself is not so much prized as the price we paid for it. …. the question that is apt to be asked about war service is not what was achieved, but what was given?”