“The summer vacation has been a busy time for many of us. Miss Penrose, with the co-operation of Miss Darbishire and Miss Walton, undertook to organise the National Registration in Oxford” SSA Annual Report, November 1915.

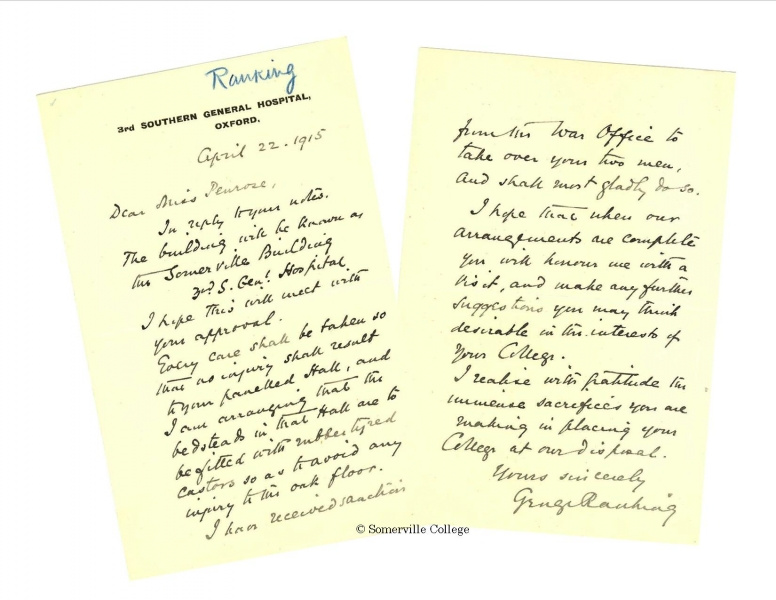

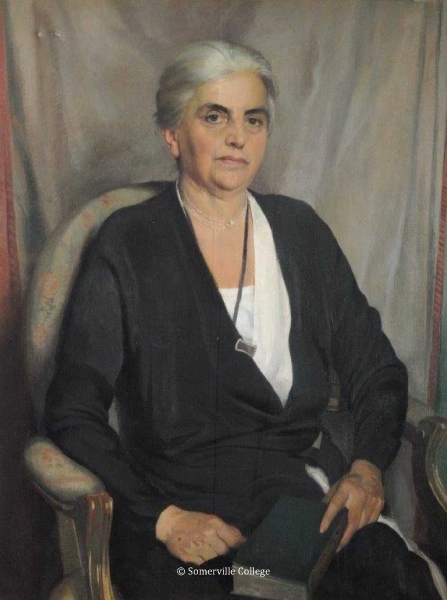

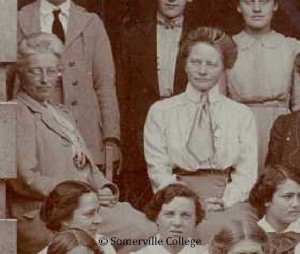

Miss Emily Penrose, Somerville’s Principal from 1907 to 1926, was as renowned for her administrative abilities as she was for her academic achievements and in the long vacation of 1915 she utilized those skills in a very particular form of war work.

In July 1915 the National Registration Act was passed, its purpose to provide the Government with accurate statistics on those available for military service, those doing essential work and those who might be able to replace enlisted men. All adults of working age (15-65), not already serving in the armed forces, were required to register on 15th August 1915.

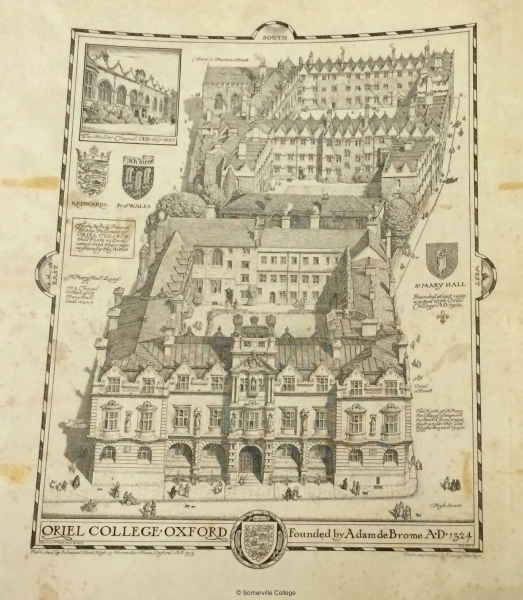

The task of registration was the responsibility of local authorities across the country and Miss Penrose was asked to organize it in Oxford. St Mary Hall was conveniently central and the SSA Annual Report noted “Old students will probably have seen with pride the numerous press notices which commented on the uniquely efficient manner in which the business of the Register in Oxford was conducted.”

Somerville’s Vice Principal, Miss Alice Bruce, spent the summer in London working for the Red Cross and Mildred Pope, the Tutor in Modern Languages, was in France with the Friend’s War Victims Relief Expedition.

The most unusual form of war work was probably that undertaken by Hilda Lorimer, the Tutor in Classics who, along with members of the other women’s colleges, set up and ran Shenberrow Camp in the Cotswolds from 5th to 18th August.

Shenberrow was the first collective undertaking of the Belgian Sub-Committee of the OWSSWS (the Oxford Women Students’ Society for Women’s Suffrage), its aim to equip applicants for relief work in Belgium with practical skills (cooking, washing and sanitation, first aid and Flemish).

The site, an ancient British fort with level ground and an excellent water supply, ‘fell into the hands of the Amazons’. Forty-four women attended, including four young Belgians who looked forward to ‘taking a share in the reconstruction of their land’ and gave instruction in Flemish. The women lived under canvas; lamb, delivered by the half-sheep on horseback, was roasted over trench fires. The daily routine included Swedish drill, tent inspection, chopping wood, collecting brushwood and digging sanitary trenches as well as lessons in first aid and how to cook economical, wholesome food. They were joined for the first couple of days by Violetta Thurstan, a Red Cross nurse, who had gone to Belgium at the start of the war, been a German prisoner and had served with a ‘Flying Column’ on the Russian front. Reactions to the camp varied, from the good humour of its occupants to the friendly assistance of the local farmer and the declaration by one baker’s delivery boy: “I wouldn’t live ‘ere, not for three pound a week!”