Somerville was the first women’s college in Oxford to attract research funding, with an endowment from Rosalind, Countess of Carlisle in 1912. The Icelandic scholar Bertha Phillpotts, of Girton College Cambridge, became the first Lady Carlisle Research Fellow in 1913. Originally appointed for five years, her tenure ended prematurely in 1917, due to the intervention of Lady Carlisle herself.

Early in the war, Bertha’s brother Owen, a diplomat, had been posted to the British Legation in Stockholm. Sweden was a neutral country and in 1916, Bertha Phillpotts visited her brother, in part for her own academic research, in part to assist him, as he was struggling to ‘settle’ both professionally and domestically (Owen was clever but chaotic). Bertha Phillpotts took on an unofficial (and initially unpaid) clerical position at the legation, also working as the head of mission’s private secretary.

Writing to Emily Penrose in May 1916, Bertha Phillpotts obviously intended her visit to Stockholm to be temporary and not for the duration of the war. She would help at the legation until the Foreign Office could send a replacement while continuing her research, realising that a longer sojourn in Stockholm could mean the end of her fellowship. By October, the situation with her brother had not improved; in particular, she had problems retaining domestic staff (Bertha mentioned the old ‘pro-German gossip’, a possible reference to an incident in 1915 when some sensitive documents, lost by Owen, were published in a pro-German newspaper). She continued her research and hoped to return to Oxford by the following Trinity Term.

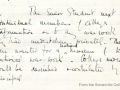

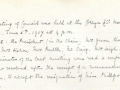

Wishing to assist by suspending the fellowship until Bertha Phillpotts could return, Somerville sought approval for this scheme from Lady Carlisle. Rosalind Carlisle’s response, in May 1917, was the opposite of the college’s position. She thought suspension of the fellowship, particularly so soon after its establishment, was contrary to the terms of the foundation and did not agree with Somerville that this followed a precedent set by male academics. Lady Carlisle believed men had no choice when called to national service whereas women did. Suspension was against the spirit of the fellowship and might pander to women who perhaps lacked steadfastness in their academic pursuits. Her opinion, once sought, could not be ignored and it was with great regret that Somerville’s Council accepted Bertha Phillpotts’ resignation on 5 June 1917.

Bertha Phillpotts spent the rest of the war as a civil servant in Sweden, employed as Private Secretary to the Head of the Legation, and received an OBE in 1918. After the war, she returned to academia and in 1922 she was elected Mistress of Girton. On her untimely death in 1932, Somerville’s Council recorded:

“Her tenure of the Fellowship was broken into by the European War, but during her three years in residence she made a memorable contribution to the life of the College by her brilliant intellect, her passionate devotion to her studies and her vital personality. The College laments the loss of a distinguished Scholar and true friend.”