By June 1916, almost two years of wartime had altered the relationship between the women’s colleges and the University more profoundly than the years of pre-war lobbying and gentle persuasion. ‘A Mess of Pottage’, the Going Down Play performed that June in the quad at St Mary Hall, was based upon the university’s war-time poverty and the consequent advantages of giving degrees to women.

By June 1916, almost two years of wartime had altered the relationship between the women’s colleges and the University more profoundly than the years of pre-war lobbying and gentle persuasion. ‘A Mess of Pottage’, the Going Down Play performed that June in the quad at St Mary Hall, was based upon the university’s war-time poverty and the consequent advantages of giving degrees to women.

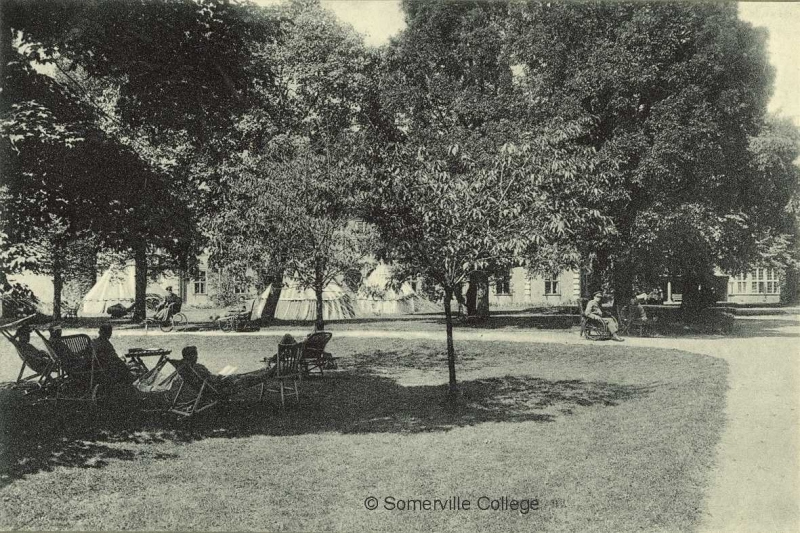

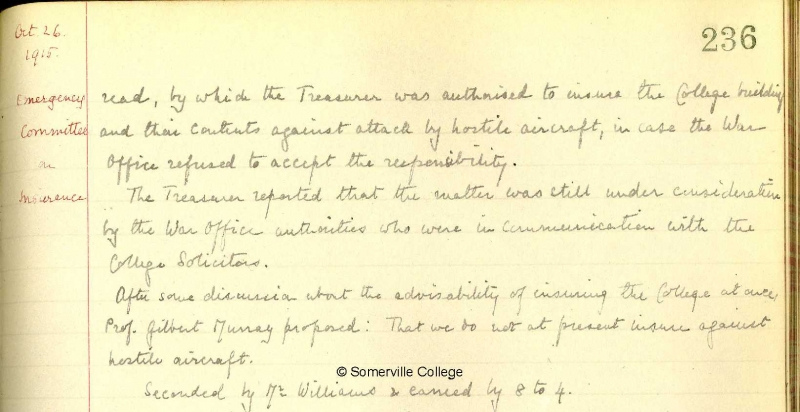

Enlistment and conscription had reduced the male student population to a quarter of its pre-war size with some of the colleges accommodating servicemen in place of undergraduates. The men’s colleges were hard-pressed financially, as the income from fees diminished. The women’s colleges became the preservers of scholastic life in Oxford, providing academic continuity via the cycle of matriculation, education and examination and generating much needed income from student fees.

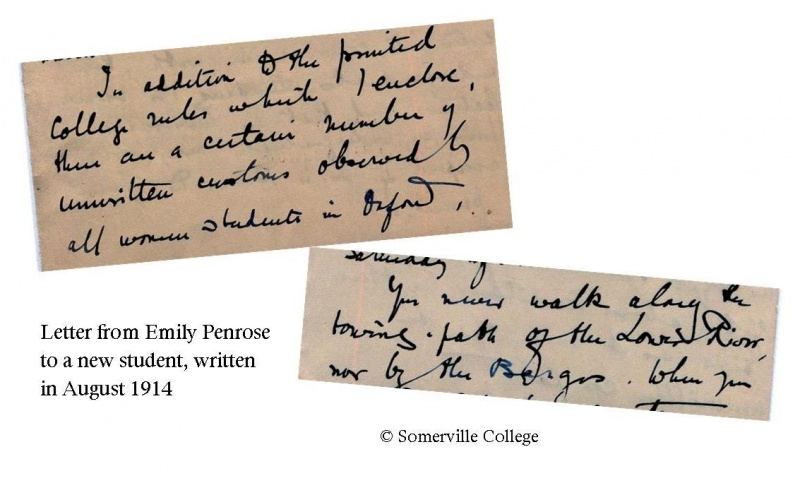

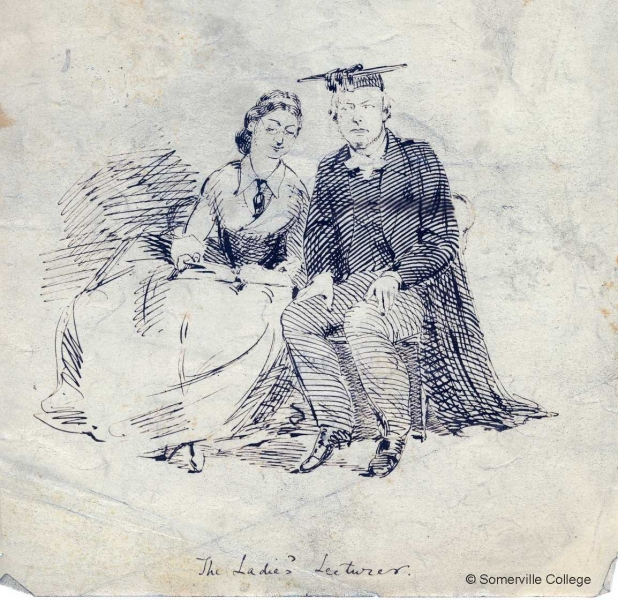

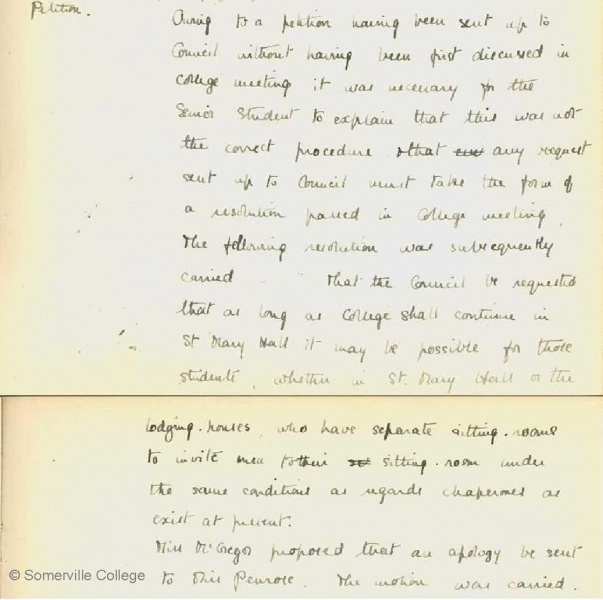

This increasing reliance on the women’s colleges led to their closer integration with the University. Women had first been invited to give University lectures in 1915; by 1916 Miss Penrose was one of six Oxford academics to sit on the Royal Commission on university education in Wales, and, that June, the admission of women to the 1st Bachelor of Medicine examination at Oxford was under consideration and being discussed by Somerville’s Council.

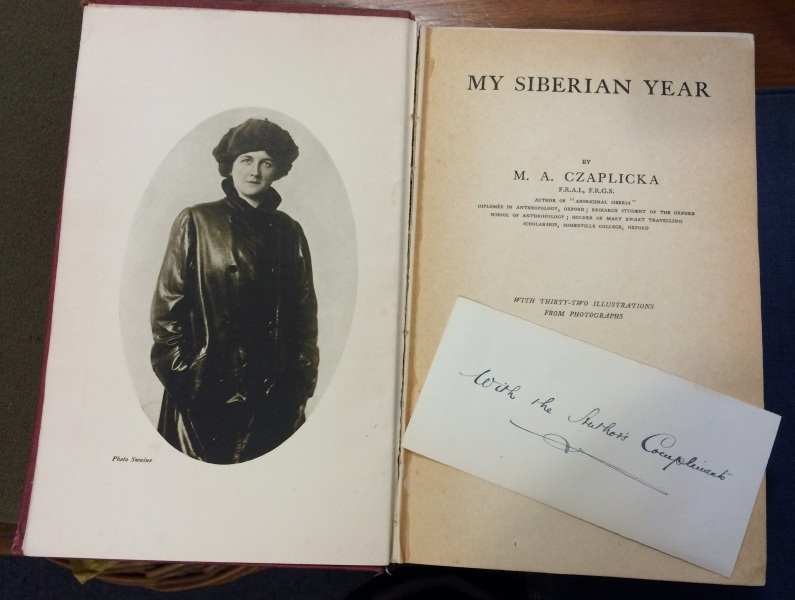

Comparatively few women trained as doctors before 1914 but by 1916 there was a shortage of qualified medics both at home and in the armed forces and the War Office was employing women doctors as Civil Medical Practitioners and as civilian officers abroad. At Oxford, women could study a science (physiology, for example) but they were not permitted to take the Bachelor of Medicine (BM) examination. Once they had finished their Oxford course, they had to train as doctors elsewhere, such as the London School of Medicine for Women at the Royal Free Hospital or the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women.

Allowing women to study medicine would assist the country, the university and the women’s colleges, who lost talented students and staff (including Somerville’s librarian Madeline Giles) forced to train elsewhere. Access to facilities and the teaching of human anatomy appear to have been particular issues but the women’s colleges held a joint conference that summer to find solutions.

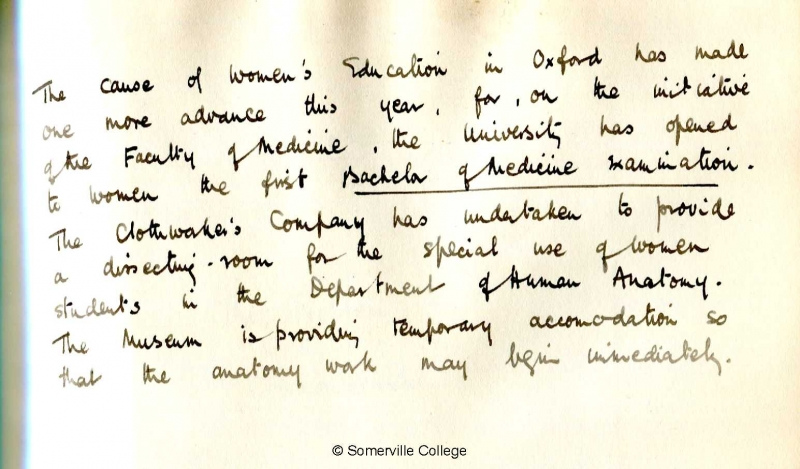

In October 1916, the Faculty of Medicine opened the 1st BM

In October 1916, the Faculty of Medicine opened the 1st BM  examination to women. The Clothworkers’ Company, which funded a number of scholarships, provided a dissecting room for the special use of women students in the Department of Human Anatomy, solving the problem of facilities. Of the first four women to graduate in medicine, two were at Somerville (Dorothy Crook and Katharine Hodgkinson).

examination to women. The Clothworkers’ Company, which funded a number of scholarships, provided a dissecting room for the special use of women students in the Department of Human Anatomy, solving the problem of facilities. Of the first four women to graduate in medicine, two were at Somerville (Dorothy Crook and Katharine Hodgkinson).

They were soon followed by two of the college’s, and the country’s, most notable medics – Cicely Williams,

They were soon followed by two of the college’s, and the country’s, most notable medics – Cicely Williams,  the pioneering paediatrician and nutritionist, who arrived in 1917 and Janet Vaughan, the haematologist and future Principal of Somerville, who came up in 1919.

the pioneering paediatrician and nutritionist, who arrived in 1917 and Janet Vaughan, the haematologist and future Principal of Somerville, who came up in 1919.