Hilda Lorimer was Somerville’s Tutor in Classics (and subsequently Tutor in Classical Archaeology).

A Scotswoman from Dundee, she became a fellow in 1896, having taken a 1st in Classics at Girton College, Cambridge. In 1914-15, she taught Vera Brittain, who wrote in Testament of Youth of Hilda Lorimer’s kindness and of her seeming desire to do more than just teach during the war. As the war progressed, Hilda Lorimer combined her scholarly duties with a number of practical national service roles, the most notable of which was also a statement of her commitment to women’s suffrage – the Scottish Women’s Hospitals (SWH). The Somerville Council minutes record that as early as May 1915, Hilda Lorimer was intending to take a sabbatical and volunteer in Serbia. Her plans were postponed due to ‘uncertainties in the Balkans’ and she instead spent the college vacations engaged in practical pursuits such as working on the land and in a munitions canteen.

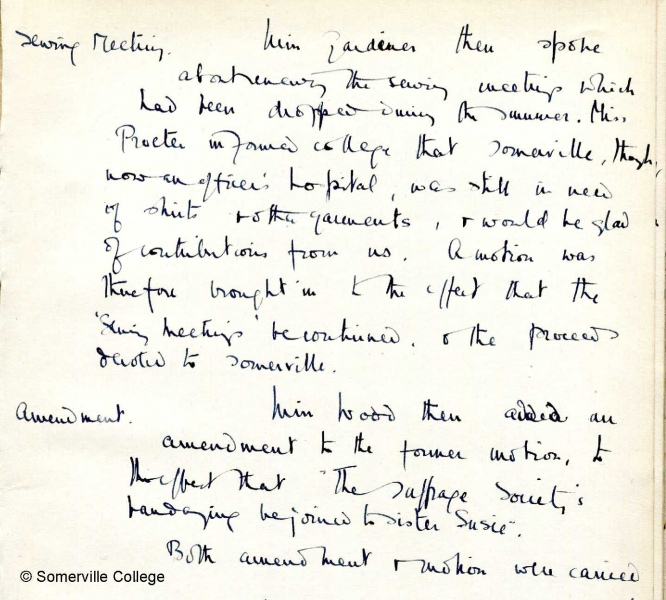

The Somerville Council minutes record that as early as May 1915, Hilda Lorimer was intending to take a sabbatical and volunteer in Serbia. Her plans were postponed due to ‘uncertainties in the Balkans’ and she instead spent the college vacations engaged in practical pursuits such as working on the land and in a munitions canteen.  She also helped Belgian refugees, most memorably as a participant in the survival training camp set up at Shenberrow in August 1915, organised by the OWSSWS (the Oxford Women Students’ Society for Women’s Suffrage).

She also helped Belgian refugees, most memorably as a participant in the survival training camp set up at Shenberrow in August 1915, organised by the OWSSWS (the Oxford Women Students’ Society for Women’s Suffrage).  In 1916 Hilda Lorimer took part-time employment in the Translations Department of the Admiralty and it was in April 1917 that she was finally able to take a 5 month leave of absence from Somerville and set out for Salonika (Thessaloniki), joining the Girton & Newnham Unit of the SWH as an orderly.

In 1916 Hilda Lorimer took part-time employment in the Translations Department of the Admiralty and it was in April 1917 that she was finally able to take a 5 month leave of absence from Somerville and set out for Salonika (Thessaloniki), joining the Girton & Newnham Unit of the SWH as an orderly.

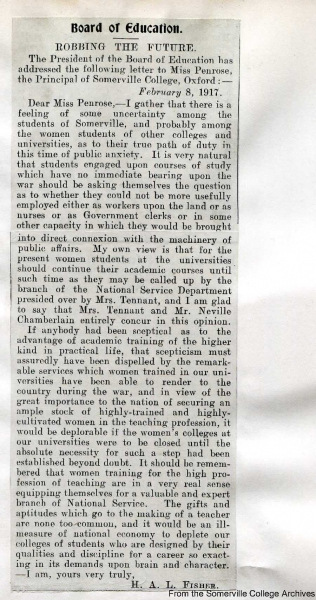

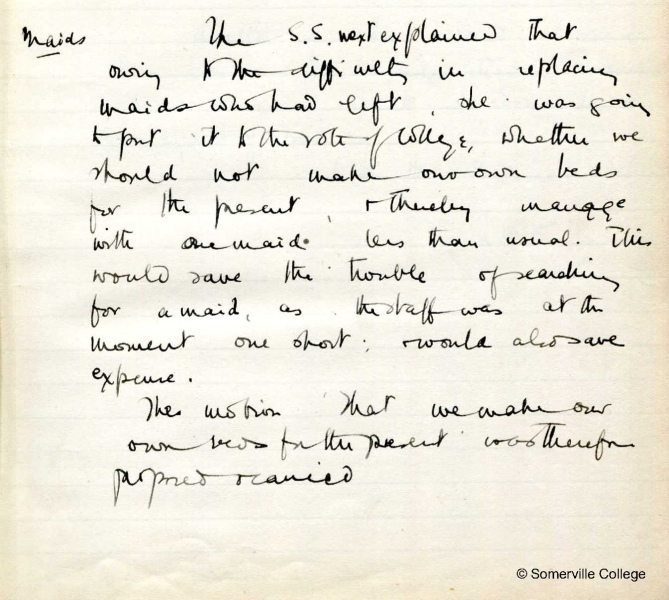

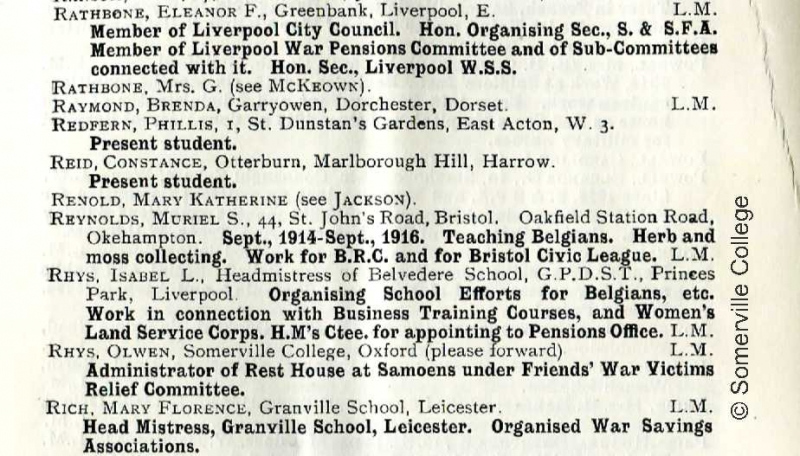

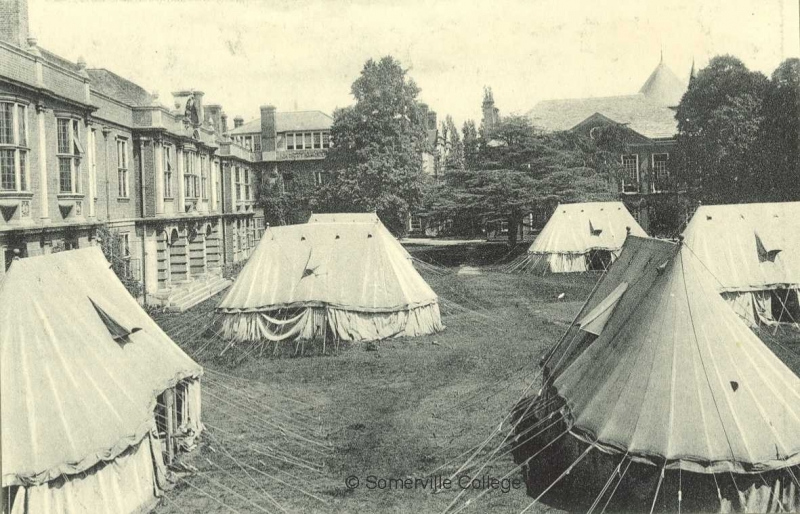

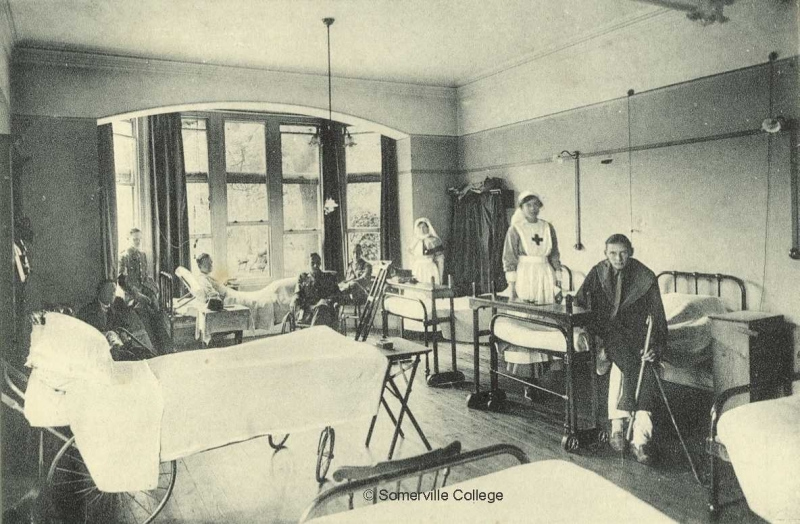

The Scottish Women’s Hospitals was one of the many voluntary organisations established at the beginning of the war but it differed crucially from most of the others, as its aims were two-fold from the outset: contributing to the war effort and promoting women’s rights. Having had their offer to assist the Army rejected by the War Office (Dr Elsie Inglis, one of the SWH’s founders, was told to ‘go home and sit still’), the SWH instead set up medical units in France, Belgium and Serbia, organised and staffed by women. Funded by the two women’s colleges in Cambridge, the Girton and Newnham Unit was based in a field hospital at Salonika. In addition to the wounded from the Serbian campaign, it treated large numbers of malaria patients.  Support staff at the SWH were expected to fund themselves and the Council minutes of 30 January 1917 indicate that the college was willing to provide Hilda Lorimer with financial assistance if needed.

Support staff at the SWH were expected to fund themselves and the Council minutes of 30 January 1917 indicate that the college was willing to provide Hilda Lorimer with financial assistance if needed.

Hilda Lorimer returned to Somerville in September 1917 and resumed her teaching duties at the college in the Michaelmas term. In 1918, she began writing on Slovenia and Yugoslavia for the Foreign Office and she went on to contribute papers on Yugoslavia and on Serbian history to the Nations of Today series, edited by John Buchan and published in 1923-4.