On 6 February 1918, the Representation of the People Act extended the right to vote to all men aged over 21 and, for the first time, to some women. To qualify, the women had to be over 30, own property or be graduates voting in a University constituency. The effects of the Act would be rapid and profound for women at Oxford.

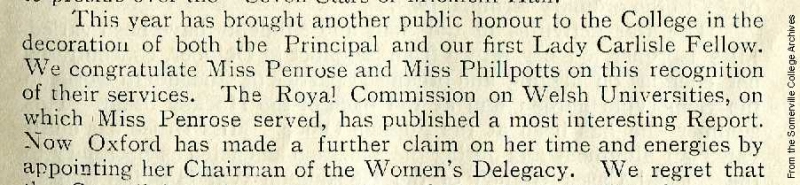

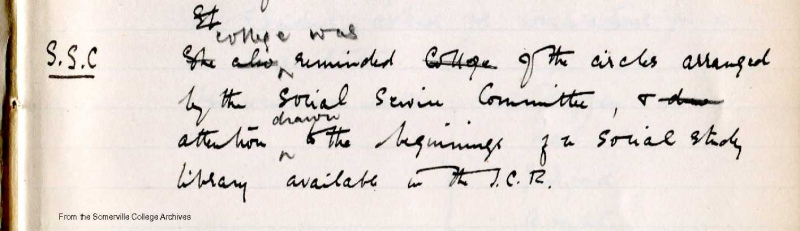

In Somerville, college life continued. The Hall Notices section of The Fritillary included Emily Penrose’s OBE, the Social Studies Circle, debates in Parliament and the achievements of the Hockey and Boat Clubs. Unusually, there was also an announcement of marriage, as on 19 February, Charis Barnett married Lieutenant Sydney Frankenburg.

Charis Barnett had come up to Somerville in 1912 to read English (see February 1914 blog). She had left Somerville for the summer vacation of 1914 and had not returned, deciding instead to train in midwifery before serving under the Friends’ War Victims Relief Committee at Samoens and later in Chalons-sur-Marne.

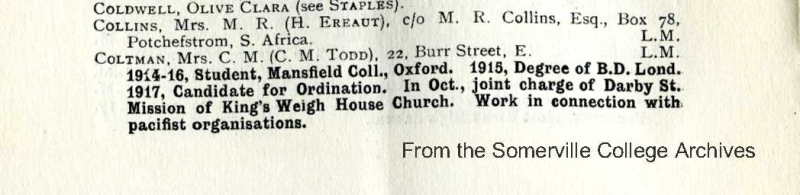

She did not return to Somerville after the war, nor did the majority of Somervillians who gave up their studies, even if originally intending national service to be of limited duration. However, Charis Frankenburg did not let the premature end to her university career scupper her academic aspirations entirely and in 1921 she matriculated and received an MA.

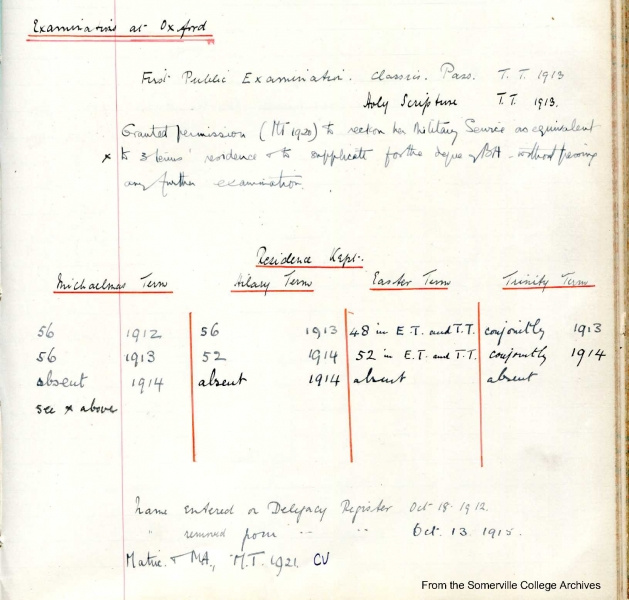

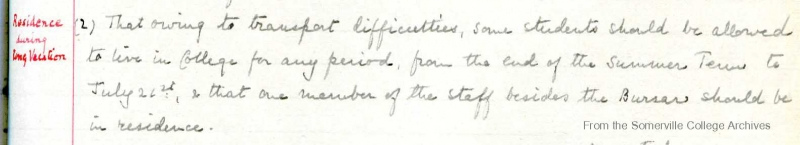

To be eligible for a degree, students had to meet various requirements including one of residence (residing for a stipulated number of weeks per term within a stipulated distance of Carfax). As hundreds of male students returned to Oxford to resume their studies in the year following the Armistice, the University decided to recognise their special circumstances and allow military service to count towards their residence.

Unusually among Somerville students and probably Oxford women more widely, Charis Frankenburg was allowed to count her war service in a similar manner; the college register records that in Michaelmas Term 1920, she was ‘granted permission to reckon her Military Service as equivalent to 3 terms’ residence and to supplicate for the degree of BA without passing any further examinations’. To have her war service included was feat enough (just three Somervillians met the residency qualifications this way), the waiving of further examinations was extraordinary. After the war, Charis Frankenburg went on to become a leading campaigner on maternity and infant welfare and, in 1926, co-founded one of the first birth control clinics in the country, in Salford.

Having led the way, women a generation later would benefit from the precedent set by war-time volunteers such as Charis Frankenburg and from the assimilation of the women’s colleges into the University after the admission of women to degrees. Post World War 2, war service was widely recognised and accepted as part of the matriculation requirements for entrants applying to Somerville as well as for students who wanted to claim a BA, having taken the shortened (2 year) war-time degree.