In 1940, the Ashmolean Museum received a sizeable bequest from the founder of Somerville College Chapel, E.G.Kemp. This included, among other things, a sum of money equalling £8,000; three oil paintings, perhaps most notably The Holy Family by Ambrosius Benson (c.1550); and a collection of her own watercolours completed while she travelled in Asia.

In order to give an indication of her experiences and interests, I reproduce a very small sample of Kemp’s own pictures below, accompanied with extracts from her travel books.

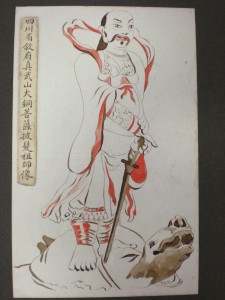

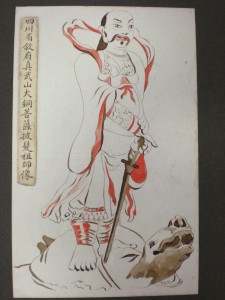

Copper Image, Suifu, China.

‘A Roman Catholic priest is deeply interested in the local divinity, which is certainly

an interesting specimen of art, if nothing more; but the priest is firmly persuaded that it is St. Thomas [the Apostle Thomas, or ‘doubting Thomas’], and takes all his friends to see it. The god is enshrined in a temple on a hillside overlooking the town. It is a most beautiful situation, but somewhat spoilt by the fact that it is entirely covered with graves. Hills are frequently utilised for this purpose, and contain thousands of graves. The gaudily painted figure is 18 feet high and 5 [and a half] feet broad, made of fine red copper. It stands on a large bronze turtle, from which, unfortunately, a good part has been stolen; the head alone is in excellent preservation. It was erected some hundreds of years ago by the Lolos or Ibien, an aboriginal tribe who then held possession of this part of the country. They believed that he was a saint who came over the seas on a turtle, and this certainly corresponds with the legend of St. Thomas going to India. It is a very truculent-looking saint, not lightly to be parted from his sword. The figure is well fenced off from view by large bars, though one has been removed, so that people can push through and get a closer look at him. While I was busy sketching, a priest came up to look, with his long hair fastened on the top of head by a carved wooden pin. The priests do not plait their hair, but simply twist it up into a sort of “bun.” A woman came up with offerings – fowl, sweets, etc. – which, after they had been offered to the god, she would take home and eat with the greater relish. This is certainly a way of killing two birds with one stone, as she was too poor to have eaten chicken on ordinary occasions. As we came down the hill we met the chief mourner of a funeral, wearing the coarsest sackcloth, which he could scarcely prevent from falling off, as it is incorrect on such occasions to gird it round the waist.’ The Face of China p.196-197.

![Mosque [Ashiho, China, May 1st, 1907], reproduced in The Face of Manchuria, Korea and Russian Turkestan, p.144](https://blogs.some.ox.ac.uk/chapel/files/2011/11/CIMG5645-225x300.jpg) ‘Near the mission there is a pretty Mosque, built exactly like a Buddhist or Taoist temple, which provides schools for boys and girls. … My sketch [of the Mosque at

‘Near the mission there is a pretty Mosque, built exactly like a Buddhist or Taoist temple, which provides schools for boys and girls. … My sketch [of the Mosque at

Ashiho] was done under considerable difficulties, for the boys had just come out of school, and would jostle up and down, and round about me on the mound of earth where I was sitting, raising such a dust that at last I was driven defeated from the field.’ The Face of Manchuria, Korea and Russian Turkestan, p.146.

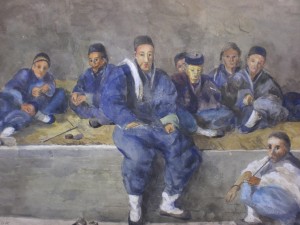

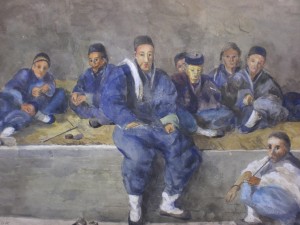

Opium Refuge, reproduced in The Face of China, p. 80.

‘Shansi [Shanxi] is one of the worst provinces of all as regards opium smoking, and the poppy is largely cultivated. In the accompanying sketch a group of patients is seen, who have come to a mission refuge to try and break off the habit. They are allowed to smoke

tobacco, but are mostly resting or sleeping on the khang; the brick bed seen in every inn and in most private houses. On the floor in front of it is seen a small ound aperture*, where the fire is red, which heats the whole khang.’ The Face of China, p.80.

*Unfortunately, my poor photography has cut this out; it is just in front of the man in white at the front right.

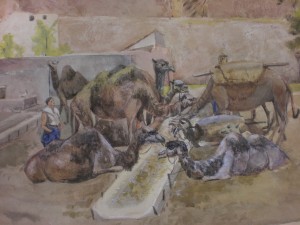

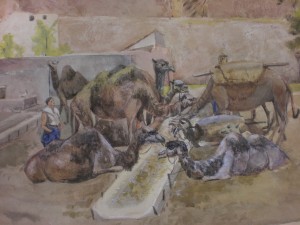

Camel Inn (1893), The Face of China, p. 74.

‘On the roads [near Pao-Ting-fu, China] we met long strings of camels carrying packs, the tail of one animal being attached to the nose of the one behind. They have inns

of their own, being cantankerous beasts, and are supposed to travel at nights because of being such an obstruction to traffic. Certainly if you lie awake you can generally hear the tinkle of their bells. They are the most attractive feature of the landscape in the north, whether seen in the streets of Peking, or on the sandy plains of Chili. My sketch was taken in the summer when the camels were changing their coats, so that the one in the front has a grey, dishevelled look, corresponding with Mark Twain’s description. He says that camels always look like “second-hand” goods; but it is clear that he cannot

know the fine stately beast of North China.’ The Face of China, p. 74-75

![Mosque [Ashiho, China, May 1st, 1907], reproduced in The Face of Manchuria, Korea and Russian Turkestan, p.144](https://blogs.some.ox.ac.uk/chapel/files/2011/11/CIMG5645-225x300.jpg)